Contact-free nanoscopy concept shows potential for investigating conductivity of materials

A team of physicists from Germany, the .S. and the U.K. managed to observe the motion of electrons from one atomically thin layer into an adjacent one with nanoscale spatial resolution. The new contact-free nanoscopy concept, which shows great potential for investigations into conducting, nonconducting and superconducting materials, will be introduced in the new volume of the science journal Nature Photonics.

Nanotechnology sounds like science fiction, but is already an integral part of modern electronics in computers, smart phones and cars. The size of transistors and diodes has reached the nanoscale, corresponding to only one millionth of a millimeter. This makes conventional optical microscopes no longer sufficient for inspecting these nanostructures. To develop innovative future nanotechnology, scientists have replaced the optical microscope with much more sophisticated concepts, such as electron or scanning tunneling microscopy. However, these techniques use electrons instead of light, which can influence the properties of the nanoscale devices. Furthermore, these important measurement techniques are limited to electrically conducting samples.

A team of physicists around Rupert Huber and Jaroslav Fabian at the Regensburg Center for Ultrafast Nanoscopy (RUN) at Universität Regensburg, together with colleagues Tyler Cocker from Michigan State University, U.S., and Jessica Boland from the University of Manchester, U.K., have introduced a new technique that can resolve electron motion on the nanoscale without electrical contact. Better still, the new method also reaches femtosecond time resolution at one quadrillionth of a second. Combining these extreme spatial and temporal resolutions make the recording of slow-motion movies of ultrafast electron dynamics on the nanoscale possible.

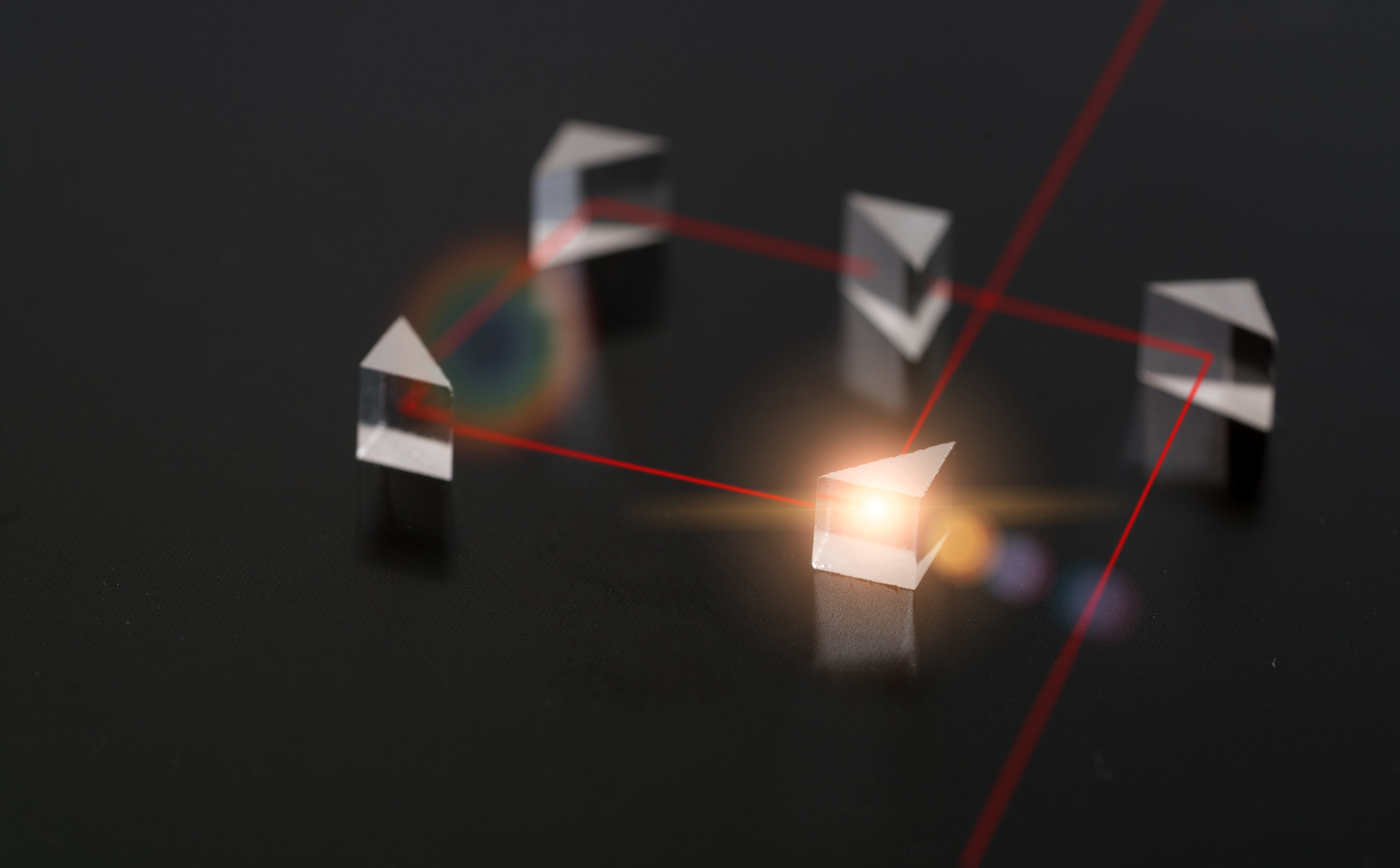

The concept behind the technique is similar to contactless payment technologies. These payment methods are based on established frequencies and protocols on the macroscale such as near field communication (NFC). Here, the scientists transferred this idea down to the nanoscale by using a sharp metallic tip as a nano-antenna, which is brought close to the investigated sample. In contrast to established techniques in which tips drive a current through the sample, the new concept uses a weak alternating electric field to scan the sample contactlessly. The frequency used in the experiments is boosted to the terahertz spectral range, approximately 100,000 times higher than the that used in NFC scanners. Minute changes in these weak electric fields allow for precise conclusions about the local electron motion within the material. Combining the measurements with a realistic quantum theory shows that the concept even allows for quantitative results. In order to achieve high temporal resolution, the physicists used extremely short light pulses to record crisp snapshots of the movement of electrons over nanometer distances.

The team chose a sample of a new material class called transition metal dichalcogenides, which can be produced in atomically thin layers, as their first test sample. When these sheets are stacked under freely chosen angles, new artificial solids emerge with novel material properties, which are prominently investigated in the Collaborative Research Center 1277 in Regensburg. The sample under study was made from two different atomically thin dichalcogenides to test the centerpiece of a futuristic solar cell. Shining green light onto the structure causes charge carriers to emerge that move in one or the other direction depending on their polarity—the basic principle of a solar cell, which converts light into electricity. The ultrafast charge separation was observed by the scientists in space and time with nanometer precision. To their surprise, the charge separation even works reliably when the dichalcogenide layers lay over tiny impurities like a mini carpet—important insights to optimize these new materials for the future use in solar cells or computer chips.

"We can't wait to record further fascinating charge transfer processes in insulating, conducting and superconducting materials," says Markus Plankl, first author of the publication.

Postdoctoral colleague and co-author Thomas Siday says, "Insights on the ultrafast transport on the relevant length and timescales will help us to understand how tunneling shapes the functionalities in a wide range of condensed matter systems."

Source. Image: Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock