Replacing lithium with sodium in batteries

An international team of scientists from NUST MISIS, Russian Academy of Science and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf has found that instead of lithium (Li), sodium (Na) "stacked" in a special way can be used for battery production. Sodium batteries would be significantly cheaper and equivalently or even more capacious than existing lithium batteries. The results of the study are published in the journal Nano Energy.

It is hard to overstate the role of lithium-ion batteries in modern life. These batteries are used everywhere: in mobile phones, laptops, cameras, as well as in various types of vehicles and space ships. Li-ion batteries entered the market in 1991, and in 2019, their inventors were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their revolutionary contribution to the development of technology. At the same time, lithium is an expensive alkaline metal, and its reserves are limited globally. Currently, there is no remotely effective alternative to lithium-ion batteries. Due to the fact that lithium is one of the lightest chemical elements, it is very difficult to replace it to create capacious batteries.

The team of scientists from NUST MISIS, Russian Academy of Science and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, led by Professor Arkadiy Krashennikov, proposes an alternative. They found that if the atoms inside the sample are "stacked" in a certain way, then alkali metals other than lithium also demonstrate high energy intensity. The most promising replacement for lithium is sodium (Na), since a two-layer arrangement of sodium atoms in bigraphen sandwich demonstrates anode capacity comparable to the capacity of a conventional graphite anode in Li-ion batteries—about 335 mA*h/g against 372 mA*h/g for lithium. However, sodium is much more common than lithium, and therefore cheaper and more easily obtained.

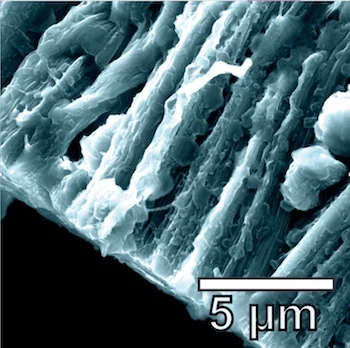

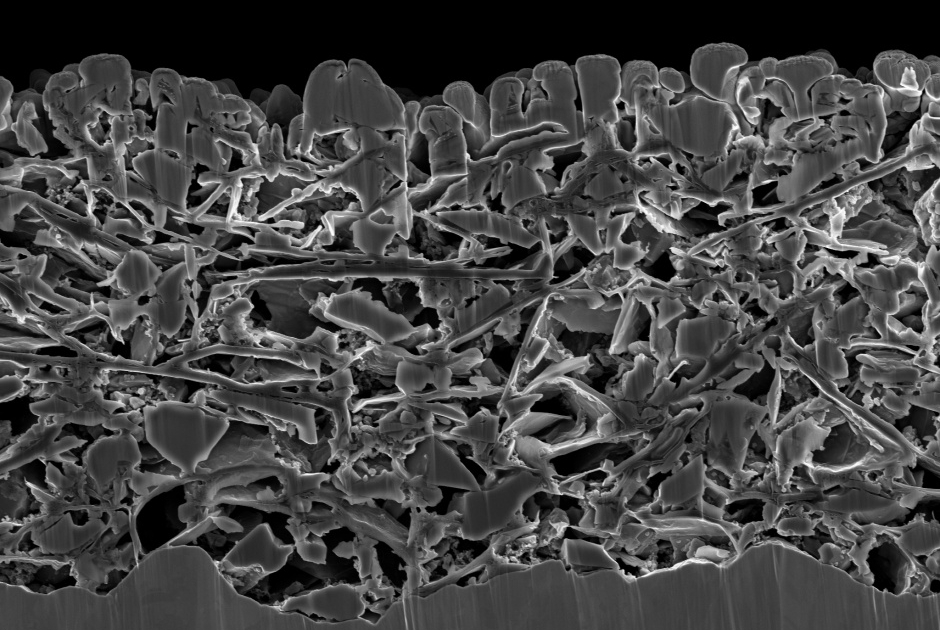

A special way of stacking atoms is actually placing them one above the other. This structure is created by transferring atoms from a piece of metal to the space between two sheets of graphene under high voltage, which simulates the process of charging a battery. In the end, it looks like a sandwich consisting of a layer of carbon, two layers of alkali metal, and another layer of carbon.

Ilya Chepkasov, researcher at NUST MISIS Laboratory of Inorganic Nanomaterials, says, "For a long time, it was believed that lithium atoms in batteries can only be located in one layer, otherwise the system will be unstable. Despite this, recent experiments by our German colleagues have shown that with careful selection of methods, it is possible to create multilayer stable lithium structures between graphene layers. This opens up broad prospects for increasing the capacity of such structures. Therefore, we were interested in studying the possibility of forming multilayer structures with other alkali metals, including sodium, using computer simulation."

Zakhar Popov, senior researcher at NUST MISIS Laboratory of Inorganic Nanomaterials and RAS, says, "Our simulation shows that lithium atoms bind much more strongly to graphene, but increasing the number of layers of lithium leads to less stability. The opposite trend is observed in the case of sodium—as the number of layers of sodium increases, the stability of such structures increases, so we hope that such materials will be obtained in the experiment."

The next step of the research team is to create an experimental sample and study it in the laboratory. This will be handled in Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research, Stuttgart, Germany. If successful, it could lead to a new generation of Na batteries that will be significantly cheaper and equivalently or even more capacious than Li-ion batteries.