Quantum dots illuminate transport within the cell

Biophysicists from Utrecht University have developed a strategy for using light-emitting nanocrystals as a marker in living cells. By recording the movements of these quantum dots, they can clarify the structure and dynamics of the cytoskeleton. Their findings were published on 21 March in Nature Communications.

The quantum dots used by the researchers are particles of semi-conducting material just a few nanometres wide, and are the subject of great interest because of their potential for use in photovoltaic cells or computers. “The great thing about these particles is that they absorb light and emit it in a different colour,” explains research leader Lukas Kapitein. “We use that characteristic to follow their movements through the cell with a microscope.”

But to do so, the quantum dots had to be inserted into the cell. Most current techniques result in dots that are inside microscopic vesicles surrounded by a membrane, but this prevents them from moving freely. However, the researchers succeeded directly delivering the particles into cultured cells by applying a strong electromagnetic field that created transient openings in the cell membrane. In their article, they describe how this electroporation process allowed them to insert the quantum dots inside the cell.

EXTREMELY BRIGHT

Once inserted, the quantum dots begin to move under the influence of diffusion. Kapitein: “Since Einstein, we have known that the movement of visible particles can provide information about the characteristics of the solution in which they move. Previous research has shown that particles move fairly slowly inside the cell, which indicates that the cytoplasm is a viscous fluid. But because our particles are extremely bright, we could film them at high speed, and we observed that many particles also make much faster movements that had been invisible until now. We recorded the movements at 400 frames per minute, more than 10 times faster than normal video. At that measurement speed, we observed that some quantum dots do in fact move very slowly, but others can be very fast.”

Kapitein is especially interested in the spatial distribution between the slow and fast quantum dots: at the edges of the cell, the fluid seems to be very viscous, but deeper in the cell he observed much faster particles. Kapitein: “We have shown that the slow movement occurs because the particles are caught in a dynamic network of protein tubules called actin filaments, which are more common near the cell membrane. So the particles have to move through the holes in that network.”

MOTOR PROTEINS

In addition to studying this passive transport process, the researchers have developed a technique for actively moving the quantum dots by binding them to a variety of specific motor proteins. These motor proteins move along microtubuli, the other filaments in the cytoskeleton, and are responsible for transport within the cell. This allowed them to study how this transport is influenced by the dense layout of the actin network near the cell membrane. They observed that this differs for different types of motor protein, because they move along different types of microtubuli. Kapitein: “Active and passive transport are both very important for the functioning of the cell, so several different physics models have been proposed for transport within the cell. Our results show that such physical models must take the spatial variations in the cellular composition into consideration as well.”

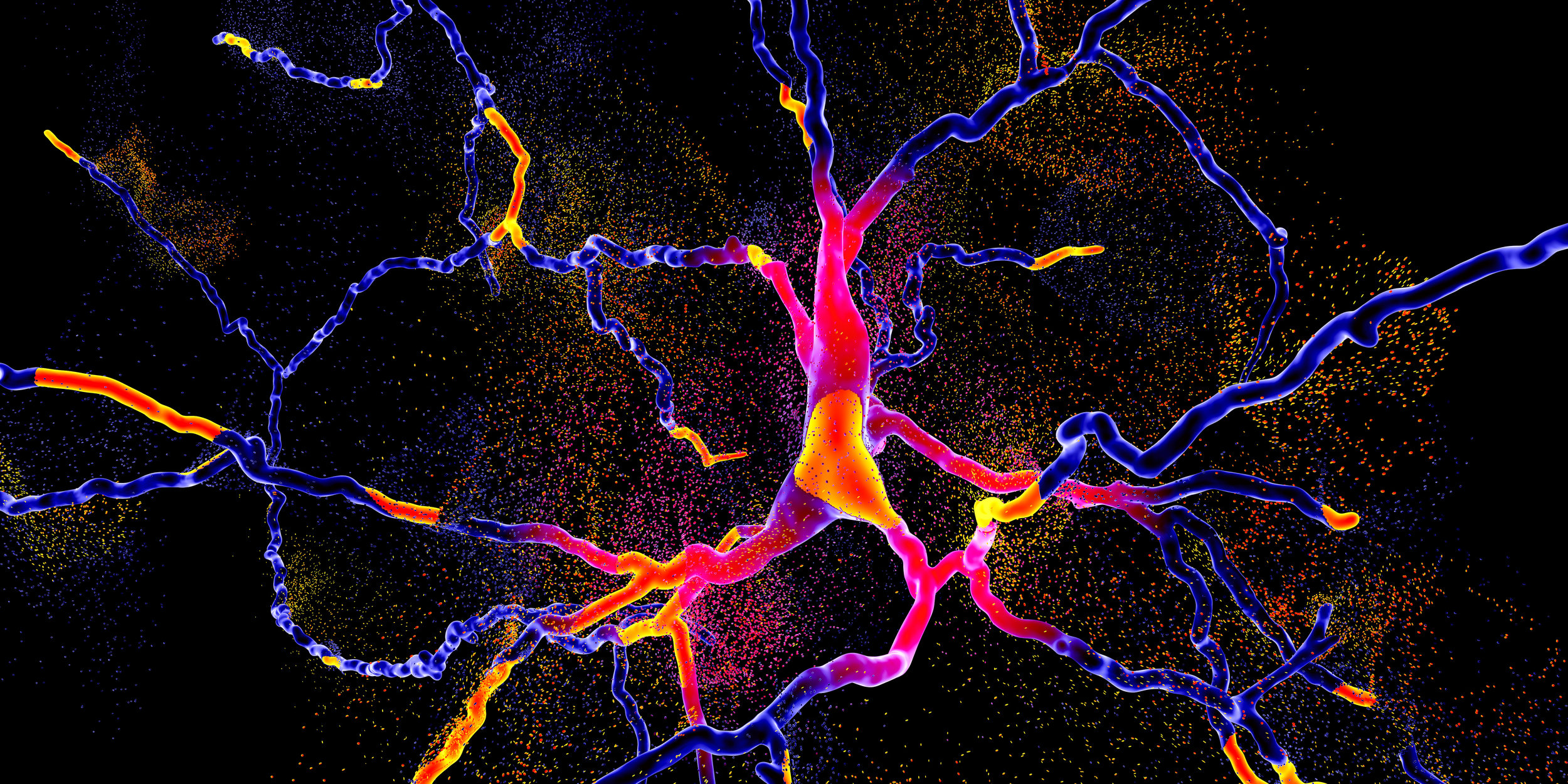

Image: The various transport processes that can be studied using quantum dots. Cyan: rapid diffusion. Red: slow diffusion in an actin network. Green: active transport by motor proteins. Credit: Anna Vinokurova